“GEGHARD”

SCIENTIFIC ANALYTICAL

FOUNDATION

2026

2026

2025-12-18

In Azerbaijani society, patriarchal relations and male dominance over women have long shaped social, economic, and everyday life. Although during the Soviet period Azerbaijani women were occasionally involved in the country’s educational sector and political processes, their appointment to party and administrative bodies—mostly in secondary positions—and their participation in political life was largely illusory. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, this situation became more pronounced. While at the beginning of 1991 women constituted about 40% of the Supreme Council in Azerbaijan, by 1992 their share had dropped to only 6%. After the 1995 elections, and again in 2005, the proportion of women deputies in parliament reached 12%.

The law On State Guarantees of Equal Rights for Women and Men adopted in 2006 did little to advance women in the country’s top state agencies. As of 2016, Azerbaijani women made up 16% of the parliament. The 2024 snap parliamentary elections brought little change: in the 7th convocation of the Milli Majlis, only 19 of the 125 deputies, around 15%, are women.

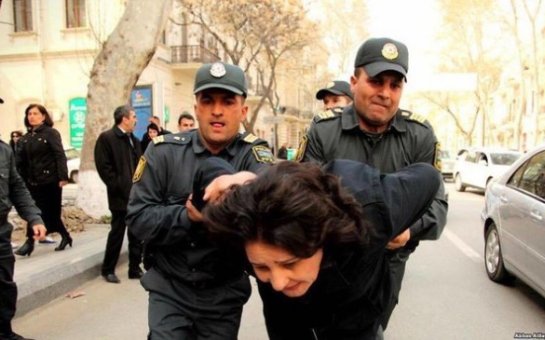

In Azerbaijan, protests related to political or religious issues, or even the defense of women’s rights, have never seen widespread participation by women. During such demonstrations, harsh treatment by law enforcement, the use of violence, surveillance, and control over personal lives have acted as deterrents for many women. A striking example is the detention and death of Faina Kungurova in 2007, a member of the Azerbaijan Democratic Party, who actively participated in protests against Heydar and Ilham Aliyevs. This happenned despite being recognized by the Council of Europe as Azerbaijan’s only female political prisoner.

The suspicious death in 2023 of member of Parliament Ganira Pashayeva, who had been highly active in politics, may also have had a discouraging effect on the political engagement of women. A native of the Tovuz region, this “Iron Lady,” as she was often called, enjoyed significant popular support and was well known to international partners. In effect, her prominence was an intolerable form of competition for the ruling family and the country’s first lady, regardless of her affiliation with the Pashayev clan.

Another example is the arrest of historian and human rights defender Leyla Yunusova, who was released following intervention by international organizations and subsequently left Azerbaijan.

More broadly, in order to avoid international criticism, state security agencies have typically subjected active female protesters to short-term, “symbolic” detention or discredited them by exposing and publicizing their private lives. In this way, the principle that “the more harmless and innocent the victim appears, the greater the psychological impact” has been put into practice.

Only liberal and at times feminist flash mobs have been participatory. Unlike overtly political demonstrations, their organizers have operated mainly on online platforms. This relative tolerance has largely been due to the fact that authorities have framed such flash mobs as apolitical, harmless, and even entertaining activities.

In the late 2000s and throughout the 2010s, several dozen organizations with feminist members were established. These included the “Azerbaijan Feminist Group,” the “Feminist Women’s Movement,” the MIL network, “Equals,” the FEMM Project’s gender programs, the feminist platform Qadınkimi.com, and others. However, they did not present themselves as feminist or political entities. From the outset, these organizations—founded by women or with women’s participation—avoided political discourse and activism. This was due to prevailing perceptions in Azerbaijani public, political (including opposition), and even academic circles, where feminists and feminism were viewed as negative and open to criticism. In addition, Azerbaijan’s ruling elite initially underestimated women’s political power.

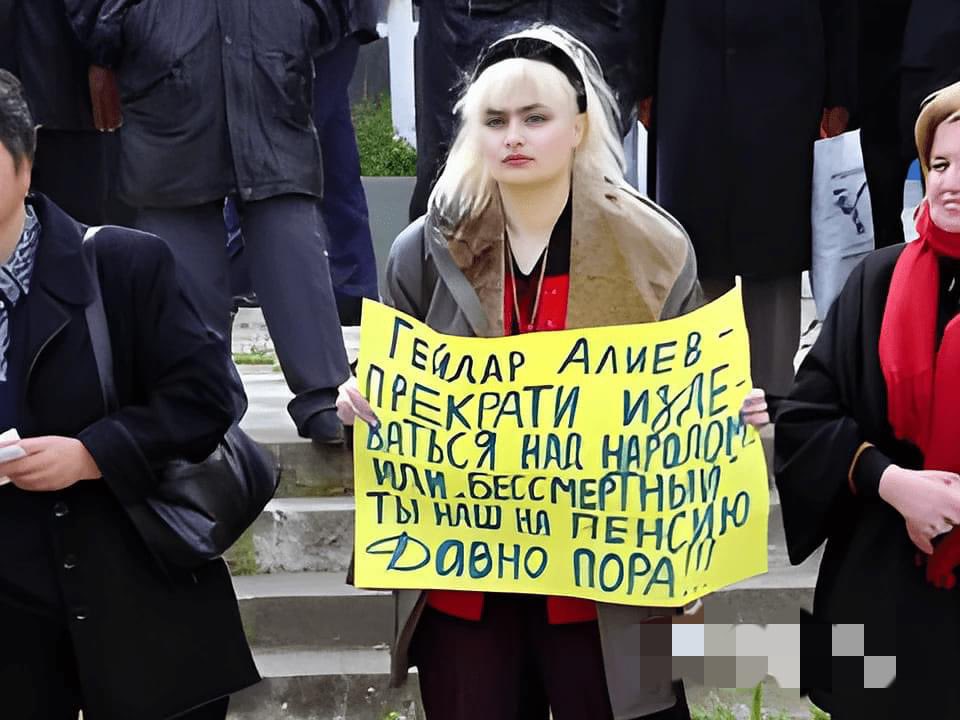

In 2019, a feminist women’s initiative group organized the first feminist march in Azerbaijan, titled “March 8 Against Violence”. Azerbaijani feminists called on women to unite in order to free society from patriarchy and male dominance, make women’s voices heard, and protect women from domestic and other forms of violence, including early marriage and femicide. The event demonstrated that a broad feminist network had already formed in Azerbaijan and that feminism and women’s issues were becoming politicized, moving from a “social/harmless” sphere into a “political/dangerous” one. It became evident that organizations established by women or with women’s participation were gradually shifting their focus away from educational and cultural issues toward feminism and, above all, toward raising awareness of gender issues, expanding the space for public discussion, and changing the negative perception of feminism within local society.

As a result, between 2019 and 2021 law enforcement agencies carried out widespread crackdowns on participants in regularly organized protest rallies and marches involving not only opposition forces but also women’s active participation. This change of approach toward women’s rights advocacy caused concern in Azerbaijan. The authorities began to fear that such active groups, with a visible audience and potential voter base, could seek to enter formal politics or exert significant influence over domestic political processes.

To disrupt this trend and foster public indifference toward the activities of active women, the Aliyev regime adopted a strategy that involved stigmatizing, humiliating, and neutralizing them by associating them with marginalized groups. Pro-government sources labeled women who spoke out about violations of their rights using terms such as “mad,” “immoral,” “degenerate,” “traitors,” “puppets of the West,” “dangerous,” and “anti-masculine,” “anti-family,” and “anti-national” elements.

Although the opposition was largely silenced after late 2019, women’s groups continued to raise women’s rights issues, particularly through March 8 events. Police responded harshly to most of these actions. An exception occurred on March 8, 2024, when security forces did not disperse a small, unauthorized rally in Baku, to the participants’ surprise. This apparent “tolerance” on the part of the authorities had clear reasons. By that time, most active women and women journalists were already imprisoned or in exile as a result of the repression that had intensified since 2023, while police forces had cordoned off the protest site. In addition, the action received little coverage, as law enforcement agencies were simultaneously conducting searches and arrests at the offices of Toplum TV, drawing the attention of the media and civil society organizations to that wave of repression.

At present, the illusion of women’s inclusion within the country’s top leadership is maintained by the first female speaker of Azerbaijan’s Milli Majlis, Sahiba Gafarova, and by the country’s First Vice President, Mehriban Aliyeva. In particular, the authorities seek to influence public opinion by highlighting Aliyeva’s role and presenting her appointment to a senior state position as a “vivid example of the appreciation of women in Azerbaijan.”

Despite assurances by Azerbaijani officials to international organizations that the country has made progress on gender equality, the reality is different. According to a UN study on gender equality in Azerbaijan, women continue to have less access to economic resources than men. The report also notes that women have fewer opportunities and less experience in participating in decision-making, both in private and public life. Claims denying discrimination against women likewise fail to withstand critics, given documented cases showing that Azerbaijani authorities apply gender-based discrimination or the threat of it against active women.

According to international media observations, attacks against women public figures in Azerbaijan are gender-biased, as they are attempts to exclude women from public life. The Azerbaijani authorities also continue to ignore calls by international organizations to release more than 350 political prisoners.

In its efforts to hold power within its own family at any cost, the Aliyev regime has effectively proclaimed Mehriban Aliyeva the “only woman” in the political arena, while marginalizing other women who show even limited political activity, including potential candidates within the ruling camp, and pushing them out of Azerbaijan’s political and public life. Moreover, the large-scale presence of women on the streets of Baku poses a threat to the ruling elite, as a struggle for rights can, through a chain reaction, evolve into a broader political struggle for power.