“GEGHARD”

SCIENTIFIC ANALYTICAL

FOUNDATION

2026

2026

2025-06-19

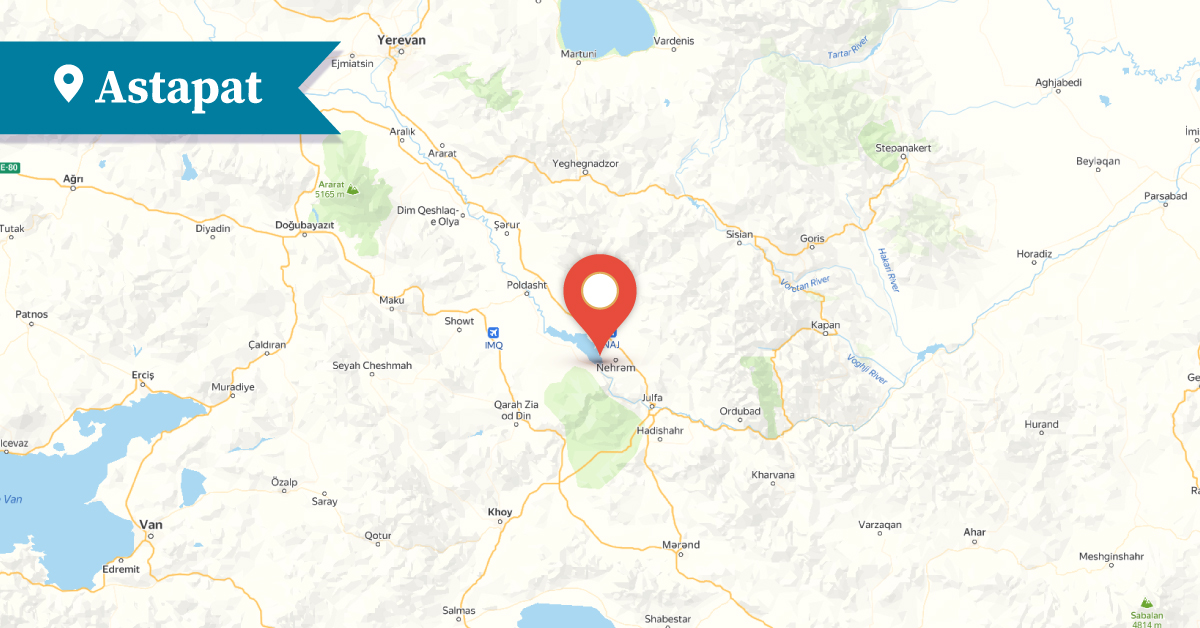

Astapat was one of the settlements in the Nakhchavan district of the Vaspurakan province. According to legend, the origin of its name is linked to the Armenian expression “Here they are enshrouded, wrapped in shrouds.” The story tells that after the Battle of Avarayr in 451 AD, the people brought the bodies of the Armenian commander Vardan Mamikonian and the other martyred heroes to the village's Karmir Monastery and enshrouded them there. However, it is said that later the princes of Maku claimed that the heroes had died in the Avarayr plain, which is closer to Maku, and thus their bodies were moved from this village to Maku. As a result of this event, the village was named Astapat.

Several researchers have also attempted to explain the origin of the village's name, offering different interpretations. One interpretation derives it from ast- meaning “strong, firm, stable” and -apat meaning “settlement” or “inhabited place.” In another case, it is explained as a compound of ast- meaning “here” and -apat, as in cases such as Astvatsapat > Astatsapat > Astapat or Azatapat > Astapat, and so on.

Astapat is first mentioned as a town-like village by the 9th–10th century historian Tovma Artsruni in his work The History of the House of Artsruni, when describing events from the early 8th century.

And in his 1806 work Geography of the Four Parts of the World: Asia…, Ghukas Inchichean noted that the majority of Astapat’s 300 households were Armenians, and only a few Persian families lived there. To describe the people of Astapat, Inchichean cites a Persian saying: “The inhabitants of Astapat adore their homes, the Tabrizis adore women, and the residents of Nakhijevan adore gold.”

Among the extensive information found in Ghevond Alishan’s work Sisakan: Topography of the Province of Syunik is the testimony of the 17th-century traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. He describes Astapat as “a very beautiful small town where every house had its own spring. There are four caravanserais here, surrounded by gardens and irrigated lands. It is the only settlement where red dye—Ronas (i.e., rubia)—is found, which the Indians use to dye their fabrics.”

The Armenian Astapat is also mentioned in modern and contemporary Armenian literature, including Raffi’s Samvel and David Bek, Sero Khanzadyan’s Mkhitar Sparapet, Suren Ayvazyan’s The Destiny of the Armenians, and other works.

Astapat was rich in monasteries—Saint Vardan, Saints Paul and Peter, Saint John, and Saint Stephen (also known as the Karmir Vank or “Red Monastery”)—all of which are considered jewels of Armenian architectural thought. Numerous Armenian manuscripts were copied and inscribed in this town. One of the oldest is Gospel Manuscript No. 382, dated 1269 and preserved in the Matenadaran. A well-known manuscript center operated at the school of the Saint Vardan Church in the 14th century. In 1379, thanks to the efforts of Maghakia Khrimetsi (Crimean) and Hovhan Vorotnetsi, a high school was established at the Astapat monastery, similar to the medieval vardapetarans (religious school). In the 1870s, Hovakim Ter-Grigoryan founded the school of the Karmir Vank, and one of its first students was Manuk Abeghyan, born in Astapat in 1865.

The people of Astapat were first displaced by the Persian crown prince Abbas Mirza. In 1811, they were resettled in a newly founded village near a plateau known as Zanglu, which was called New Astapat, also referred to as Tazagyugh or Tazakend. Abbas Mirza built a fortress on the original site of Astapat, naming it after himself—Abbasabad. This relocation marked the beginning of the continuous migration of Astapat’s inhabitants to other villages and towns in Armenia. Tragically, this once-thriving Armenian settlement ceased to exist from the first half of the 19th century.

However, in New Astapat—on the lands belonging to the Karmir Vank—Armenians from Armenian-inhabited areas of Iran were relocated to compensate for the lack of local inhabitants. By the early 20th century, the village had a population of 3,443 people, of whom 480 were Iranians and the rest Armenians.

Between 1918 and 1920, the people of Astapat were subjected to Turkish-Tatar attacks and massacres. Hamazasp Vardanyan, a native of the village of Shkhmamdud in Nakhijevan, described the Turkish-Tatar massacres in Astapat in his Memoirs as follows:

“In 1918, the Turks took 234 Armenians from the village who had not fled, into captivity. They forced them into labor in various locations, and once they were exhausted, they shot them. Part of the captives—120 people—were taken to rebuild the collapsed bridge over the Nakhijevan River. Another 114 were taken in the direction of Julfa to restore bridges and roads damaged by floods.”

Despite all this, the residents of Astapat continued to live in the village, establishing a collective farm named after Stepan Shahumyan and engaging in craftsmanship. Cultural life in the village was also vibrant.

After the signing of the 1963 agreement between the Soviet Union and Iran (regarding the construction of a hydroelectric power station on the Araks River), the Armenians left the village in 1971, and it was abandoned. New Astapat, with its historical-architectural monuments, residential houses, and history, was submerged under water.

If Astapat had existed for 1,360 years, the life of New Astapat or Tazagyugh lasted only 160 years. The 1,520-year history of this Armenian village in Nakhijevan was silenced in the context of Soviet Azerbaijan’s economic priorities.

Bibliography

Ghevond Alishan, Sisakan, Venice, 1898.

Ghukas Inchichian, Geogrpahy of the Four Parts of the Word, Asia, Europe, Afirca and America, Volume 1, Venice, 1806.

A. Ayvazyan, The Epigraphic Heritage of Nakhijevan, Vol. III, Goghtn District, 2007

Poghos Poghosyan, Astapat: The Armenian Land along the Araks, Yerevan, 2005.

G. Grigoryan, Astapat and Its Monasteries, Etchmiadzin: The Official Journal of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin of the Catholicosate of All Armenians, IX/XII, 1963, pp. 29–35.

Morus Hasratyan, The Architectural Complex of the Astapat Monastery, Patmabanasirakan Handes (Historical-Philological Journal), No. 1, 1975, pp. 126–148.