“GEGHARD”

SCIENTIFIC ANALYTICAL

FOUNDATION

2026

2026

2025-08-15

The Aliyev administration possesses a broad toolkit for restricting freedom of speech and the press. Beyond blocking media outlets and limiting access, manifestations of press unfreedom include the arrest of journalists and acts of physical violence and harassment against them. In Azerbaijan, there are two main mechanisms of violence against journalists: direct physical violence and the filing of lawsuits by state bodies or officials against media outlets, their editors, or correspondents. In the first case, attempts are aimed at preventing the dissemination of information about corruption and other illegal activities through the threat of force. In the second case, filing lawsuits and securing their enforcement through a flawed judicial system allows authorities both to restrict journalists’ activities (also in the future) and to deny the veracity of the accusations made.

Physical violence against journalists — abduction, murder, beating

Both in Azerbaijan and internationally, the murder of Elmar Huseynov, editor-in-chief of the Azerbaijani opposition magazine Monitor, in 2005 caused a significant outcry. Huseynov was engaged in human rights advocacy and was known for his critical articles about government officials and the family of President Ilham Aliyev.

In 2006, several journalists were subjected to physical violence. Baheddin Heziyev, editor-in-chief of the opposition newspaper Bizim Yol and vice-president of the Popular Front of Azerbaijan party, was abducted and beaten as a way of “urging” him to stop writing critical articles. Fikret Huseynli, a correspondent for Azadliq (Freedom), was also abducted and beaten by unknown individuals, which resulted in his death. There were signs of violence on his body: broken fingers and stab wounds on the neck.

Azadliq journalist Nicat Huseynov was similarly attacked and stabbed. At the same time, Ali Orucov, press secretary of the opposition National Independence of Azerbaijan party, was pursued and beaten. It should be noted that these journalists were also engaged in reporting on the corrupt activities of high-ranking officials.

In 2007, the same fate befell Uzeyir Ceferov, editor of the opposition newspaper Gundelik Azerbaijan and a war journalist, as well as journalist Süheyle Qemberova from the Impuls newspaper. In 2008, Azadliq’s 25-year-old correspondent Agil Khalil and journalist Emin Huseynov, president of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), were also subjected to harassment and violence.

Violence against journalists occurred not only because of publishing anti-government articles but also directly during journalistic coverage. For example, in January 2009, Yeni Musavat journalist Afghan Mukhtarli was beaten by law enforcement officers while covering a rally in front of the Israeli embassy. At the same time, National Security officials in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic arrested and assaulted independent journalist Idrak Abbasov.

While taking photos for an investigative article on the “luxurious villas on the outskirts of Baku” (belonging to Transport Minister Ziya Mammadov), Yeni Musavat’s 21-year-old journalists Elmin Badalov and Anar Gerayli were attacked by unidentified men.

Defamation, espionage, treason: legitimate charges or political retribution?

Opposition journalist Eynulla Fatullayev, who was persecuted for years, was sentenced in 2007 to 11 years in prison on charges of defamation, terrorism, incitement of ethnic hatred, and tax evasion. Before his sentencing, Fatullayev had founded two well-known opposition newspapers, Real Azerbaijan and Gundeli Azerbaijan, which were closed in May 2007. He was accused of publishing an article in the newspaper about the “Khojaly massacre” and later an online article in which he allegedly disrespected the memory of the Khojaly victims, questioning the Azerbaijani official version of the events. In 2011, Fatullayev was released under an amnesty and received an international award for press freedom.

In another case, editor Ganimat Zahidov and young activists Emin Milli and Adnan Hajizadeh, who criticized government policies on social media, were imprisoned on hooliganism charges following a staged fight. G. Zahid’s brother, a well-known satirist and Azadliq journalist Mirza Sakit, were sentenced in October 2006 to three years in prison on drug trafficking charges. The brothers were not even allowed to attend their father’s funeral.

In 2007, espionage and treason charges were brought against Novruzali Mamedov, editor-in-chief of the Talyshi Sado newspaper and a prominent advocate for the cultural rights of the Talysh community. In June 2008, Mamedov was sentenced to ten years in prison but died in 2009 at the Central Hospital of the Penitentiary System from heart failure.

In December 2007, five journalists were released under a general amnesty. Three of them had been imprisoned for defamation (Yashar Aghazade, Rovshan Kebirli, and Faramaz Novruzoglu), while the other two, Rafik Tagi and Samir Sedegetoglu, were charged with incitement of religious hatred for allegedly insulting the Prophet Muhammad in their articles. Amnesty International recognized them as “prisoners of conscience.”

In 2008, a lawsuit was filed against Leyla Yunus, director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, and lawyer and editor-in-chief of the Femida 007 newspaper, Ayub Kerimov. Kerimov had referred to the Ministry of Internal Affairs as a “nest of criminals” in an interview given to the opposition Azadliq newspaper. In 2010, the court confirmed Kerimov’s guilt for defamation. In 2018, Kerimov was found dead in his home in Baku, allegedly from a gas leak.

Sardar Alibayli, editor-in-chief of the Nota newspaper and correspondent Faramaz Novruzoglu were also convicted of defamation in 2007 and 2009. In 2010, Novruzoglu was again arrested on charges of calling for mass disobedience on his Facebook page.

In 2010, Mirjafar Seidov, the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Organized Crime Department, filed a criminal complaint against Muzaffar Bakhishov, a practicing lawyer and trial monitor for the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE). Bakhishov had been involved in defending the rights of several political prisoners. Likely for this reason, in 2016 the Bar Association revoked his license and submitted a petition to the Narimanov District Court to suspend Muzaffar Bakhishov’s legal practice.

In June 2010, Ramiz Mehdiyev, Head of the Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan, filed a civil lawsuit against the independent weekly Khural, allegedly seeking compensation for damage to his honor, dignity, and moral reputation. Subsequently, in 2011, the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Avaz Zeynalov, was arrested.

In 2007, Jalal Aliyev, a member of the ruling party and uncle of t Ilham Aliyev, filed a lawsuit against Rovshan Mahmudov, editor of the Mukhaliifat newspaper, and journalist Yashar Aghazadeh, who were later convicted of defamation and insult.

Restrictions on freedom of speech intensified particularly on the eve of the parliamentary elections on November 7, 2010. Thereafter, both parliamentary and presidential election campaigns were marked by acts of violence against journalists.

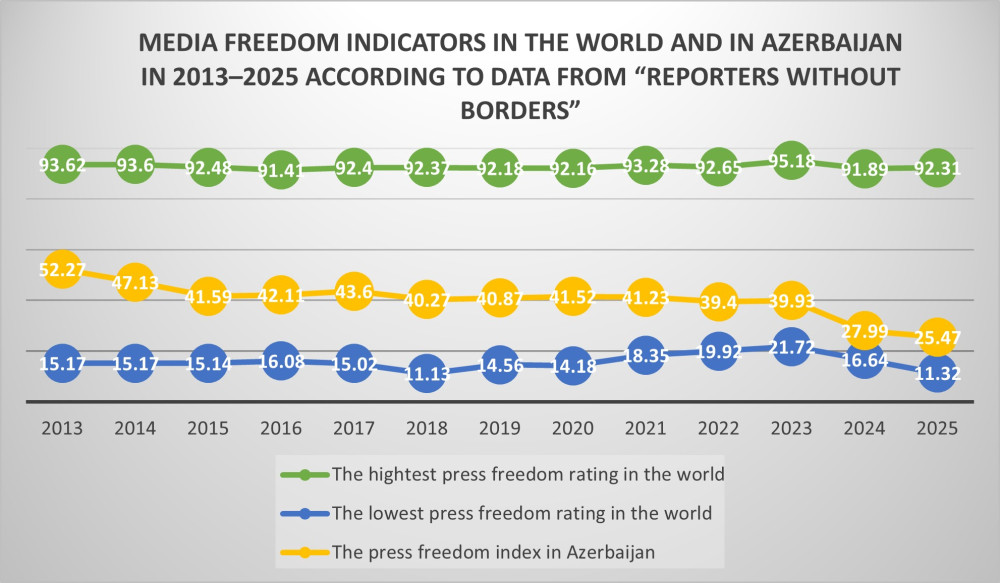

The data not only confirm but also reveal the crisis of press freedom in Azerbaijan. An analysis of the annual reports by Reporters Without Borders shows that, compared to other countries, Azerbaijan has experienced a continuous decline in its rankings. The organization calculates its media freedom index based on a combination of five components: the political and economic context, legal framework, socio-cultural context, and safety. Therefore, the lower the media freedom index, the lower the political freedom, the weaker the socio-cultural development, the more disproportionate the legal framework governing the sector, the more unhealthy the economic environment, and the higher the likelihood of pressure and repression.

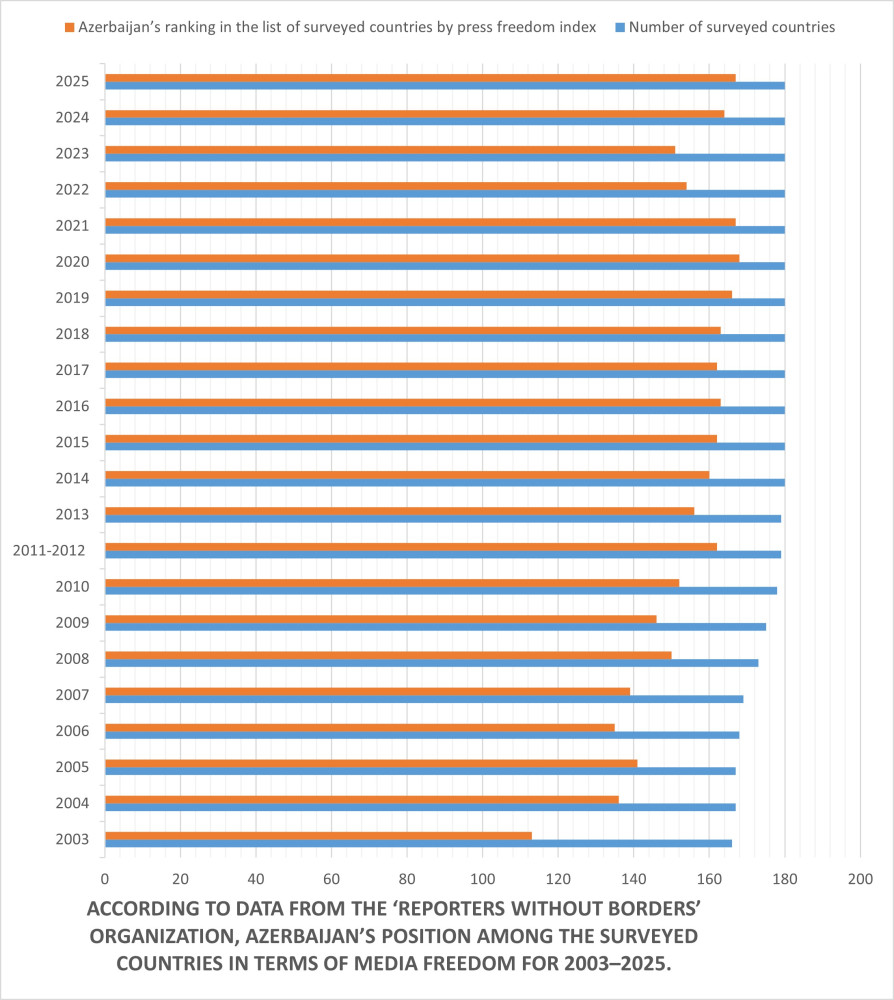

As seen in Chart 2, among the 180 countries observed between 2003 and 2025, Azerbaijan has consistently occupied low positions, ranking among the twenty countries with the highest indicators of unfreedom. For instance, in 2020, Azerbaijan ranked 168th out of 180 countries; in 2024, it was 164th; and in 2025, it is projected to be 167th.

In 2024, the Azerbaijani media freedom score differed from the worst score (16.64) by only 11.35 points. Countries that usually follow Azerbaijan include Belarus, Iraq, Vietnam, North Korea, and Afghanistan.

Another noteworthy aspect is that Azerbaijan’s press freedom index tends to decline particularly during presidential and parliamentary elections. For example, in 2018, due to the presidential elections, the media freedom index decreased by 3.33 points compared to the previous year, falling from 43.60 to 40.27. In 2024, it declined from 39.93 by 11.94 points, reaching 27.99. The situation was even more concerning after the 2010 parliamentary elections, when the index jumped from 56.3 in 2010 to 87.25 in 2011–2012, causing Azerbaijan to drop from 152nd to 162nd place in the country rankings.

Violence against media outlets and journalists accompanied the entire electoral process—both the preparatory phase, when efforts were made to minimize criticism directed at the electoral process, and the post-election phase, when attempts were made to prevent criticism of already committed election fraud. World Economics set Azerbaijan’s press freedom index at 12.2 out of a possible 100.

In 2003, Freedom House had already classified Azerbaijan as a “not free” state based on its press freedom indicators. According to the same organization, in 2017 and 2018 Azerbaijan was categorized as “partly free” based on internet freedom, with scores of 42 and 40 out of 100, respectively. By 2019, the score had declined to 39, reaching 34 by 2024.

According to the Cato Institute’s “Human Freedom Index 2021,” in 2019 Azerbaijan ranked 127th out of 165 countries, with a personal freedom score of 5.96 and a press freedom score of only 3.9.

In general, press freedom is an important indicator of a country’s political and socio-cultural situation. The lower the press freedom index, the more restricted political and civil rights are, and the more vulnerable the mechanisms for protecting human rights become. Therefore, it is not difficult to predict how human rights and freedoms are realized in Azerbaijan, a country that presents itself as a center of “multiculturalism,” expresses concern for nature conservation, and claims to restore “historical justice.”

This situation has been repeatedly highlighted by internationally respected human rights organizations. Organizations such as Freedom House, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International have consistently addressed issues of human rights in Azerbaijan, including press freedom and violence against journalists. Despite these reports, the “lack of press freedom” characteristic of Ilham Aliyev’s quarter-century rule shows signs of only deepening.

To be continued…