2025

2025

2024-09-25

Atropatene (Old Persian: Āturpatkān, Middle Persian: Āturpātākān, Classical Persian: Āḏarbāijān and Āḏarbāigān, Akkadian: Aδorbāiγān, Arabic: آذربایجان, and its Turkicized form: Azerbaijan) is a historical region located in the northwest of present-day Iran.

This region now corresponds to the East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan (in Persian: Azarbāijān-e Sharqī, Azarbāijān-e Gharbī), and Ardabil provinces of Iran. The name Atropatene originated from the name of the commander Atropates. From ancient times until the Arab conquest, this region was a political entity, first under the Sassanian Empire and then under the Caliphate. However, the heart of the region was the mountainous territory east of Lake Urmia, with the ancient summer city of Gandzak, which corresponds to the present-day city of Takht-e Soleyman in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran. At the time of the Arab conquest, the capital of Atropatene was Ardabil, which the Armenian historian Ghewond mentions as "Artavet"[1]. Later, the main center became the city of Tavriz/Tabriz, known as Davrejh in Armenian sources.

The toponym of Atropatene, and later the transformed Azerbaijan, awaited a different history from the beginning of the 20th century. The "Transcaucasian Muslim Republic," proclaimed on May 26, 1918, was later renamed the "Azerbaijan Democratic Republic." This new entity included the former Iranian khanates, including Baku, Shirvan, Ganja, Talysh, Derbent, and Quba, which had been annexed to Russia by the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). In 1920-1921, the region was Sovietized, and Soviet Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia joined the Soviet Union as part of the Transcaucasian Federation in 1922. In 1936, the Transcaucasian republics were included in the USSR as separate union republics. The 1937 Soviet Azerbaijan Constitution also enshrined the official language of the country as "Azərbaycan dili - Azerbaijani language," meaning "Azerbaijani," while the academic literature still uses the form "Azeri" (Azeri (brill.com)), which is a Turkified version of the Iranian "azari," meaning "Atropatenian, belonging to Atropatene." In Azerbaijan, "Azeri" acquired not only the function of a language name but also an ethnonym.

Certainly, both the adoption of the name "Azerbaijan" for the administrative unit in the 20th century and the use of the term "Azeri" for the language had a political undertone aiming at appropriating the history and culture of Atropatene and the Atropatenians, creating an artificial "Azerbaijani" cultural identity. It is important to note that Iranian researchers, drawing attention to the creation of the same-named administrative unit north of the Arax River and the use of the ethnonym and language name "Azeri," have criticized these steps in academic and popular literature, considering them far-reaching expansionist actions.

Atropatene is one of the territories that has consistently been a bearer of Iranian culture and a center of Iranophone since ancient times, despite the fact that today, alongside Iranian dialects, Turkic languages also exist in Atropatene. As for the Arran and Shirvan regions located north of the Arax River, researchers sometimes unify the processes of Turkification in these two parts, while in Atropatene, Arran, and Shirvan, this process took place in different ways and at different paces. When speaking about the spread of Turcophone, it is important to note the fact that the spread of the new Turkic language in nomadic plains and urban centers had different courses: in the former, it was rapid, while in the latter, encountering significant resistance, it went through phases of bilingualism, and sometimes even trilingualism.

Overall, studies show that until the end of the Iranian Safavid dynasty, the Turkification of Atropatene and Arran was far from complete, although it is still ongoing today. Moreover, in Atropatene, the transformation is only linguistic, as culturally it remains entirely Iranian. The hypothesis that the Turkification of these regions supposedly ended at the end of the Seljuk or Mongol rule is particularly untenable.

Pre-Islamic Atropatene was one of the centers of Zoroastrianism. Here, in Takht-e Soleyman, the Zoroastrian sanctuary of Adur-Gushnasp, one of the fire temples of Zoroastrian Iran, has survived to this day. Atropatene, being independent or semi-independent before finally becoming part of the Sassanid state, was always one of the centers of Iranian culture and the Iranian language.

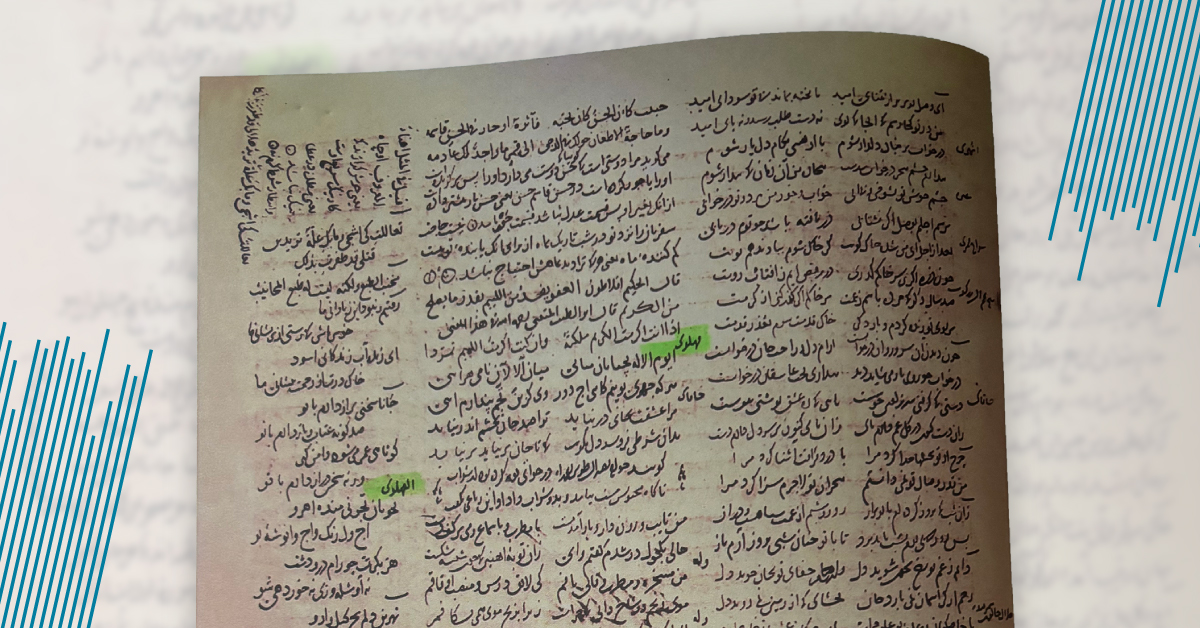

The first mentions of post-Islamic Atropatene, as well as Arran, and information about Iranian culture and the Iranian language (some of which we will present here) are contained in the works of Arab geographers. First, let us cite the mention of Ibn al-Muqaffa, an Arabic-speaking Persian writer (died in 759), that Pahlavi (referring to Middle Iranian dialects) was also the language of the inhabitants of Atropatene. This language was spoken in the territory that included Isfahan, Ray, Hamadan, Mah Nahavand, and Atropatene[2].

The 10th-century geographer Ibn Istakhri (d. 957) wrote that in "Azerbaijan and Arran, they speak Persian (al-fāresīya) and Arabic." The author notes that "an exception is the vicinity of Dabil/Dvin, in the neihbourhoud of this city, they speak Armenian, and in the land of Barda/Partav the speak Arran language"[3].

Another 10th-century author, Al-Muqaddasi, included Atropatene and Arran in the 8th division of his geographical zones[4]. He noted, "The languages of the 8th zone are Iranian". And as the renowned researcher C. E. Bosworth recorded, "North of the Arax, a distinct, presumably Iranian dialect of Arran, which Ibn Hawqal called al-Raniya, survived for a long time." Ibn Hawqal also attested to the existence of the Iranian language "al-azariya"[5].

The Arab historian Al-Masudi (d. 956) wrote that the borders of the Persian lands extended to the Alborz Mountains, Atropatene, Arran, Qabala, Darband, Ray, Tabaristan, Maskat, Shabaran, Gorgān, Abaršahr, Nishapur, Herat, Marv, and other parts of Khorasan, as well as Sistan, Kerman, Fars, and Ahvaz... All these lands were once a single kingdom, under one ruler and with one language..., although the language gradually changed... Nevertheless, the language is one, as its letters are written in the same way and used in the same manner. Thus, there were different languages - Pahlavi, Dari, Azari, but they are all Persian[6]. Masudi testifies that in the 10th century, in Arran and Azerbaijan or Atropatene, there was only Iranian presence, citing the name of a local Iranian language, Azari, and noting that in Arran, Darband, or Partav the population spoke Persian, that is, Iranian, languages.

The story recorded by Samani in the12th-century book, “Majma’ al-ansab,” about Abu Zakariya Khatib Tabrizi (d. 1109) and his teacher Abu’l-Ala Ma’arri, is another mention of the existence of an Iranian language in Atropatene in the 12th century. According to this source, Khatib Tabrizi, who was originally from Atropatene, met a fellow countryman in Maarat al-Numan (Syria), where he was studying. The countryman had entered a mosque to pray and was speaking Azari. With his teacher’s permission, Khatib Tabrizi talked with his countryman in the Azari language[7].

Nasir Khusraw's travelogue (11th century), which includes a story about his meeting with the Azari or Atropatenian poet Qatran Tabrizi, provides further evidence of the native Iranian language of Atropatene. Nasir Khusraw's encounter with the poet Qatran took place around 1059 in Tabriz. He writes, "He wrote good poetry but did not know Persian well. He came to me. He brought the collections of Manjiki and Daqiqi[8], read them to me and asked the meanings of unfamiliar words. I explained them, and he wrote them down. At the end, he read his own poems"[9]. Nasir Khusraw's assertion that Qatran did not know Persian suggests that being a native speaker of the Azari dialect, he was not proficient in the classical Persian of Khorasan and therefore turned to Nasir Khusaw for help.

Medieval historical sources concerning the Iranian nature of Atropatene provide significant evidence that Turkic elements had not yet penetrated this region before the 11th century. It should also be noted that it was from this period that a new phase of the spread, strengthening, and development of Persian literature, Persian-speaking civilization, and Iranian culture began. Only after the Safavid dynasty did the Turkic-Oghuz language spread in Atropatene alongside Iranian culture and language.

[1] Ghewond, History, translated, introduced, and annotated by Aram Ter-Ghovondian, edited by S. S. Arevshatyan, "Soviet Writer" Publishing House, Yerevan, 1982, pages 87-88.

[2] Ebn al-Nadīm, Fehrest, v. 1, 2009, 1/1։ 32

[3] Zukā Yahya, Zabān-e āzarī”, in: Jestārhāyī darbāre-ye zabān-e mardom-e Āzarbāygān, Mahmud Afshār, Tehran, 1923։ 5․

[4] Moqaddasī, Aḥsan al-taqāsīm, Tehran, 1982։ 259․

[5] Bosworth C. E., Azerbaijan iv. Islamic History to 1941, in: EI, Vol. III, Fasc. 2-3։ 225․

[6] Mas‘ūdī, Kitāb al-tanbīh wa al-ishrāf, Tehran, 1894։ 78․

[7] Zukā Yahya, Zabān-e āzarī”, in: Jestārhāyī darbāre-ye zabān-e mardom-e Āzarbāygān, Mahmud Afshār, Tehran, 1923։ 6․

[8] Iranian poets of the 9th-10th centuries

[9] Khosraw Nāser, Book of travels, translation, introduction and annotation by W. M. Thackston. New York: Persian Heritage Series N 36, 1986։ 6․