2025

2025

2025-03-26

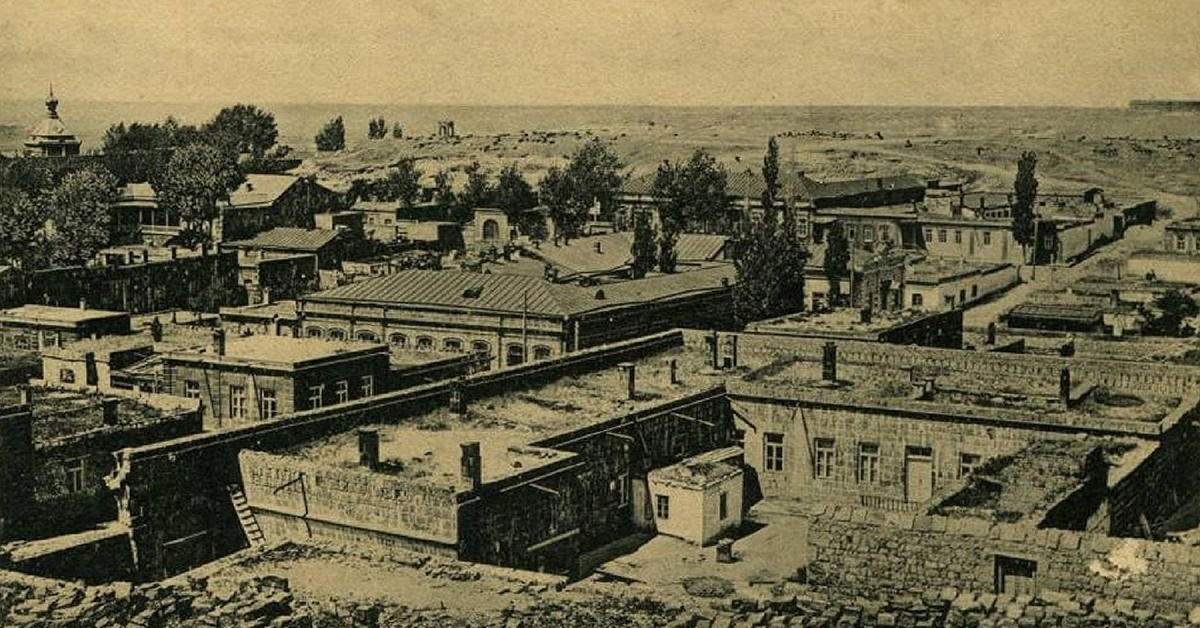

Kumayri-Gyumri

The establishment of foreign rule in Armenia, in addition to its demographic, socio-economic, cultural, and political consequences, has also had another no less dangerous effect—the replacement of Armenian toponyms, which was carried out through borrowings. According to Hrachya Acharyan's data, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Constantinople dialect contained about 4,000 Turkish words, the Van dialect—2,100, the Karabakh dialect—700, and the Yerevan dialect—up to 800[1].

The greatest and most dangerous influence exerted by Turkic languages was on the toponyms of historical Armenia—settlements, geographical locations, Christian sacred sites, and others. The Turkification of place names began in the 13th century and became more frequent in the 16th–17th centuries, in parallel with the establishment of Ottoman and Safavid rule.

he appropriation of Armenian place names occurred at the conversational level, where they were simply adapted to the phonetic characteristics of the Turkish language, acquiring a new sound. For example: Agarak – Ekrek, Aghstev – Aghstafa, Gavar – Gever, Karkar – Gyargyar, Harjis - Yayji, Dzagedzor – Zangezur, Shahaponk → Shahbuz, Shirak – Shoragyal, Vank' – Fenk', Kumayri → Gyumri, Kars → Ghars, etc.

There were also borrowings through calquing, where a word was created by imitating the structure of a corresponding unit in another language, in this case, Armenian. This category of toponyms forms the largest group: Aznvadzor – Gyozaldara, Aghjkaberd – Ghızghala, Amulsar - Ghısırdagh Areguni – Gyuney, Tsaghkut → Gyullija, Karmiraghbyur – Ghızılbulagh, Dzoragyugh → Darakend, Mokhrots – Kyomurlu, Jermuk → Istisu, Sev Lich → Gara Gyol, etc. The process also included semantic-phonetic calquing, where Armenian names adopted into Turkish retained both their phonetic structure and meaning, closely matching the original: Aghberk – Aghbulagh, Aghkhasar - Akhidagh, etc.

There are cases of place name duplications where only the suffixes have been translated into Turkic, while the original name has been preserved—for example, Ayriget - Ayrichay - Ayrisu, and so on.[2]

It was also common to give new names to settlements in an attempt to erase their national identity. Even Christian holy sites were renamed.

While in the medieval period the Turkification of toponyms was spontaneous, later, with a better understanding of its strategic significance, it became intentional and targeted.

The original Armenian versions of toponyms can be found in numerous historiographical sources and maps of the time, including Ottoman ones.[3]

The Young Turk authorities also placed great importance on the altering "non-Muslim" toponyms. The "Regulations on the Settlement of Migrants" adopted on May 13, 1913, was aimed at the systematic Turkification of place names in the Ottoman Empire. The decree issued by Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Empire's Minister of War, on January 5, 1916, ordered to Turkify Armenian, Greek, and Bulgarian place names in the Ottoman Empire.[4] The authorities of the Musavat, Soviet Azerbaijan, and the Republic of Azerbaijan implemented the same policy, originally adopted by the Sultanate and later by the Young Turk and Republican Turkey, in the eastern part of the South Caucasus and in the Armenian settlements under Azerbaijan's control.

Thus, through the distortion and appropriation of Armenian toponyms, an attempt was made to erase and eliminate the history of the Armenian people and appropriate their historical and cultural heritage.

[1] Hr. Acharyan, The Influence of Turkish on Armenian and Turkish Loanwords in Armenian, Vagharshapat, 1902. Hr. Acharyan, History of the Armenian Language, Part 2, Turkish Loanwords in Armenian, Yerevan, 1951, p. 270.

[2] See: N. Poghosyan, The Turkification of the Toponyms of Historical Armenia, Sion, Jerusalem, 2001, April-May-June, pp. 141-147.

[3] See the works of Ruben Galichian and Karen Khanlaryan.

[4] L. Sahakyan, The Policy of Turkification of Armenian Toponyms in the Ottoman Empire and Republican Turkey, Vem Pan-Armenian Journal, Yerevan, 2010, No. 1, pp. 83-96.