2025

2025

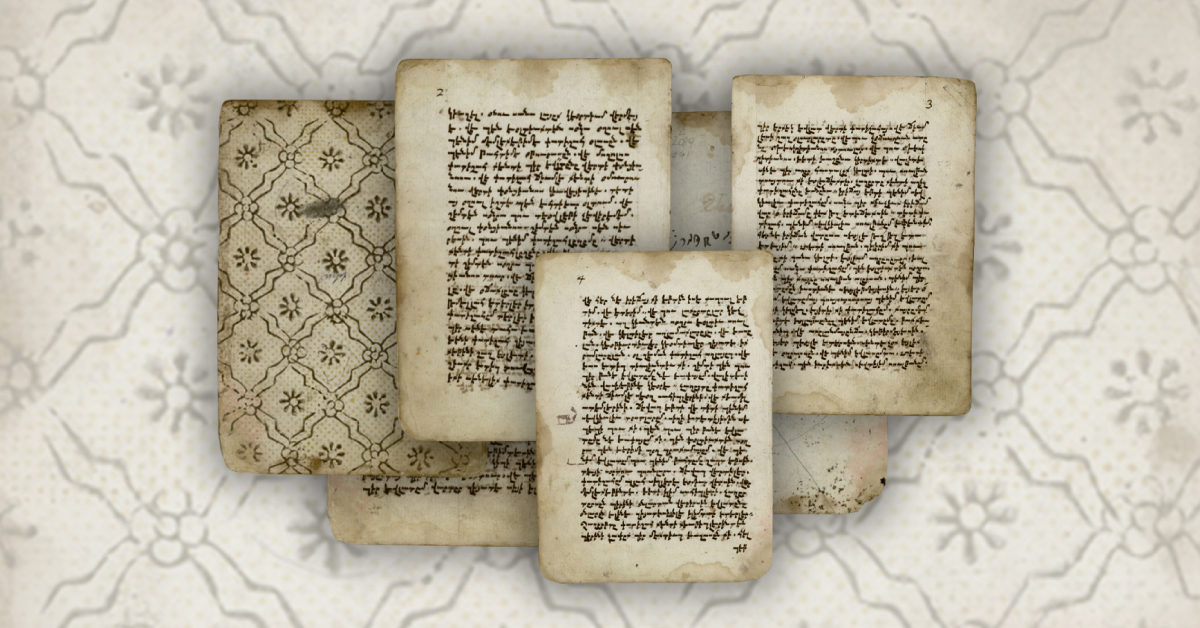

The Armeno-Turkish text production began in the 14th century with manuscripts, and from the mid-18th century onwards, it expanded through printed materials in the Ottoman Empire and several European cities. The significant volume of Armeno-Turkish printed works demonstrates that this was not a marginal or “exotic” phenomenon, but rather a commonplace aspect of cross-cultural exchanges in late Ottoman cities like Istanbul, Izmir, Aleppo, Jerusalem, as well as in European cities such as Paris, Rome, Venice, Vienna, and Trieste. The academic interest in Armeno-Turkish literary production grew in Armenia, in Europe in the early 20th century and in Turkey, particularly in the 1980s, when the study of folk literature gained traction. More recently, scholarly focus has extended to diverse genres, including literary works, life books (diaries), and investigations into newspapers and magazines from that period.

In addition to the religious texts that form the core part of the Armeno-Turkish corpus, it is important to note that a considerable number of translations in Turkey, particularly during the 18th to 20th centuries, were produced solely in Armeno-Turkish. Among this variety of works, translations held a predominant role, and there is a wealth of Armeno-Turkish versions of European literary works, such as French and German bestsellers, which were popular across communities in the late Ottoman period. This indicates the presence of bilingual or even trilingual actors, translators, and publishers, who were producing translations for Turkophone Ottoman Armenians and Ottoman Muslims (including Turks and Arabs) who were able to read Armenian script.

Multidimensional Studies of Armeno-Turkish Literature: Comparative analyses of the diverse body of Armeno-Turkish works can offer new insights into the literary landscape of the late 19th-century Ottoman Empire. Armeno-Turkish literature must be studied in relation to (Western) Armenian and Ottoman Turkish literary traditions. In this context, we should consider Armeno-Turkish texts as part of Armenian culture, established and developed within the Ottoman Empire and beyond, reflecting the mobility of knowledge and the appropriation of ideas. Moreover, we should take into account Armenian literary and cultural traditions respectively.

Another important dimension of Armeno-Turkish was its role in education, evidenced by a range of schoolbooks and religious literature intended for educational use. Yet, Armeno-Turkish was not limited to religious instruction. It often served as a mediating language for translations into Ottoman Turkish, and it was common for Ottoman Muslims to learn Armenian script in order to access translated Turkish literature more easily. This highlights the unique position of Armeno-Turkish texts across various genres, as they catered to a wide and diverse readership. The production of Armeno-Turkish texts offers an opportunity to examine the multi-religious environment of the Ottoman Empire and beyond, shedding light on the role of sacred languages in different religious communities and their relationship to vernacular languages.

Moreover, as mentioned before Armeno-Turkish has different registers and place of print. This phenomenon can reveal inconsistencies in terms of orthography expressed in Armeno-Turkish text production. It is not a secret, that Armeno-Turkish earlier interpreted as ‘dialectical peculiarity’ that was thoroughly criticised by Hrachya Acharyan. Who would have known that just a few decades after the Language Reform of 1928–1929, this vernacular found its way into the rulebooks of Standard Turkish?

Armeno-Turkish texts preserved strong influences of Western Armenian pronunciation, incorporated local dialects, and displayed a rich diversity in terms of registers and genres. The notion of Armeno-Turkish was interpreted as a “mixed” or entangled phenomenon or was considered as practical and “functional style”. To our opinion, it is an evolving concept that warrants further exploration through case studies that have been largely overlooked.

Armeno-Turkish literature is not only of interest to literary scholars and linguists but also offers researchers a valuable window into the transcultural and transregional dynamics of the Ottoman Empire. It sheds light on how Armenians within a complex web of intersecting knowledge and languages were able to create, preserve their culture.

Recommended literature on the topic:

1.Armin Hetzer: Dačkerēn-Texte: Eine Chrestomathie aus Armenierdrucken des 19. Jahrhunderts in türkischer Sprache. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1987.

2.Aysu Akcan, Hülya Çelik, Yavuz Köse and Ani Sargsyan: “Digital Preservation, Publishing and HTR of Armeno-turkish Manuscripts, Printed Books and Newspapers from the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna (MEKHITAR)”, Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 9, no. 2 (2022): pp. 67-75.

3.Bedross Der Matossian: “The development of Armeno-Turkish (Hayatar T’rk’eren) in the 19th Century Ottoman Empire”, Intellectual History of the Islamic World, Leiden(?): Brill, 2019, pp. 1-34.

4.Edith Gülçin Ambros, Hülya Çelik, and Ani Sargsyan: “Intertwined Literatures: Karamanlı, Armeno-Turkish, and regular Ottoman versions of the Köroğlu Folk-tale”. In Balta, Evangelia (ed.) Literary and Cultural Crossroads in the Late Ottoman Empire. Istanbul: Boyut, 2024: pp. 1-54.

5.Hülya Çelik and Ani Sargsyan: Introducing Transcription Standards for Armeno-Turkish Literary Studies, “DIYÂR, 3, no 2 (January 1, 2022), pp. 161-189.

6.Johann Strauss: “Is Karamanli Literature part of a “Christian-Turkish (Turco-Christian) Literature”?” In Balta, Evangelia and Kappler, Matthias (eds.). Cries and Whispers in Karamanlidika Books. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Karamanlidika Studies (Nicosia, 11–13 September 2008). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp.155–200.

7.Johann Strauss: “Who Read What in the Ottoman Empire (19th-20th centuries)?” Arabic Middle Eastern Literature 6/1 (2003), pp. 39-76.

8.Kevork Pamukciyan: Ermeni Kaynaklarından Tarihe Katkılar. Vol4., Istanbul, Aras Yayıncılık, 2003.

9.Kubra Uygur: “Understanding a Hybrid Print Media and Its Influence on Public Opinion: The case of Armeno-Turkish Periodical Press in the Ottoman Empire, 1850-1875” PhD thesis University of Birmingham, UK, 2021.

10.Laurent Mignon: “Bir Varmış, Bir Yokmuş: Kanon, Edebiyat Tarihi ve Azınlıklar Üzerine Notlar” in Ana Metne Taşınan Dipnotlar, Istanbul: Iletişim, 2009: 121-132.

11.Laurent Mignon: “Lost in Translation. A few remarks on the Armeno-Turkish novel and Turkish Literary Historiography”. Between Religion and Language: Turkish- Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire. Eds. Evangelia Balta, Mehmet Ölmez. Istanbul: Eren Yayınları, 2011, pp. 111-123.

12.Masayuki Ueno: “One Script, Two Languages: Garabed Panosian and His Armeno-Turkish Newspapers in the Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Empire”. Middle Eastern Studies 52, No. 4 (2016), pp. 605-622.

13.Murat Cankara: “Armeno-Turkish Writing and the Question of Hybridity”. An Armenian Mediterranean: Words and Worlds in Motion. Eds. Kathryn Babayan and Michael Pifer. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 173-191.

14.Murat Cankara: “Rethinking Ottoman Cross-Cultural Encounters: Turks and the Armenian Alphabet”. Middle Eastern Studies 51:1 (2014), pp. 1-16.

15.Sebouh D. Aslanian: ““Prepared in the Language of the Hagarites”: Abbot Mkhitar’s 1727 Armeno-Turkish Grammar of Modern Western Armenian”. Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 25 (2016), pp. 54-86.